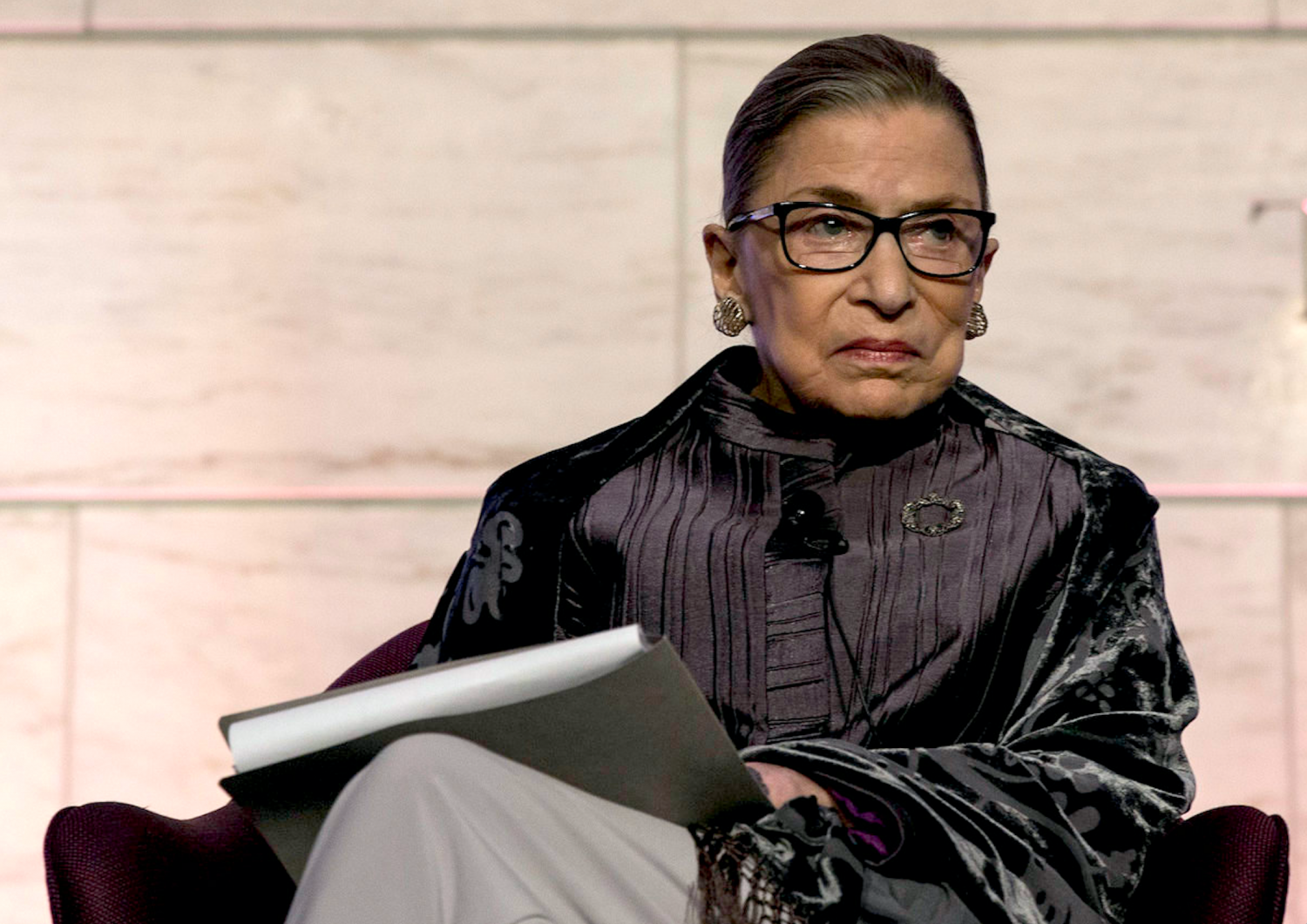

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a pioneer for women’s equality and the architect of a consequential legal strategy to dismantle systemic discrimination against women.

Years later, with the Supreme Court opinion she authored requiring the State of Virginia to allow young women into the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) — along with her dissent in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire that led to passage of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act — Justice Ginsburg built upon that legacy and establish herself as an undeniable giant in the fight for women’s rights.

The impact of Ginsburg’s contributions to civil rights, however, extends far beyond women’s rights. Building on the work of Thurgood Marshall, Ginsburg developed arguments and blazed a trail used by many others to halt discrimination and advance the rights of marginalized groups. As one example, Lambda Legal’s current cases challenging restrictions on the military service of people living with HIV — cases that could well end up before the Supreme Court — echo the strategy and arguments advanced by Ginsburg on behalf of women.

Like the strategy of incremental change Ginsburg used to advance women’s rights, the legal rights of people living with HIV have advanced incrementally. In the mid-1980’s, HIV advocates searched for a legal framework for fighting discrimination. After enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act provided that structure in 1990, the battle for nondiscriminatory treatment moved incrementally from access to pools, schools, and basic services to employment nondiscrimination for (among others) food service workers, first responders, and healthcare workers.

This decades-long campaign has now finally arrived at what may be the “holy grail” in terms of HIV employment discrimination — the United States military. In a series of lawsuits, Lambda Legal is challenging express policy that enables the Pentagon — the world’s largest employer — to discriminate against people living with HIV. The U.S. military wants to prevent service members from deploying — and to start kicking some of them out — despite the tremendous medical advancements and lack of transmission risk even in combat.

And because the Americans with Disabilities Act does not apply to the Armed Services, our lawsuit relies upon the same legal protection — the equal protection component of the Constitution — that Ginsburg used to fight discrimination against women. In fact, it seeks “heightened scrutiny” for policies singling out people living with HIV, just as Ginsburg sought for women in the early to mid-1970’s (and successfully secured in 1976).

Several of the military’s arguments against service members with HIV are similar to those used against women who wanted to serve in roles traditionally reserved for men.

The military argues it is concerned for the health of the service members living with HIV. Despite evidence to the contrary, military leadership claims service members with HIV are too vulnerable to the challenges and deprivations that come with the austere environment of deployment and that being in combat will so distress them they will forget to take their medications.

Military leaders also claim they could not possibly be engaged in discrimination against service members with HIV because they do not generally discharge them and provide them with excellent medical care, demonstrating that they bear them no ill will. But the notion that discrimination must be motivated by animus or malice toward the group in question was dismantled by the many cases involving discrimination against women.

Discrimination against service members with HIV is motivated by, among other things, outdated notions about their capabilities and purported inability to adapt to the deployed environment — the same things that motivated the military’s discriminatory policies against women.

The Pentagon has even trotted out the argument that the other service members will not want to serve alongside service members with HIV and may become hostile toward them if they learn about their HIV status. This argument holds water no better than when used against women or LGBT people who wanted to serve in the military. The failure to prevent discrimination by other employees is never a satisfactory reason for an employer to engage in discrimination.

Lambda Legal’s cases challenging the military’s discriminatory policies toward people living with HIV may one day end up before the U.S. Supreme Court. Though she will not be there to adjudicate them, it will be easier to prevail because of the legacy of Justice Ginsburg’s work. Her legacy, however, is in danger because of Trump administration nominees across the judiciary who are hostile to the rights of women, LGBTQ people and others. That is why Justice Ginsburg’s dying wish was not to be replaced by a Trump appointee.

Lambda Legal will continue to fight for justice for — people living with HIV and LGBTQ people on all fronts, but there is no doubt that the notorious RBG will be sorely missed.