Ever since our oldest daughter started daycare four years ago, the beginning of May has been tinged with a bit of dread.

We knew that we’d need to have that conversation – once again – with the center’s teachers, to make sure that they remembered that not all families are cookie-cutter. Some kids, like our daughter, have two moms. And some kids don’t have any moms, but are no less a family because of that.

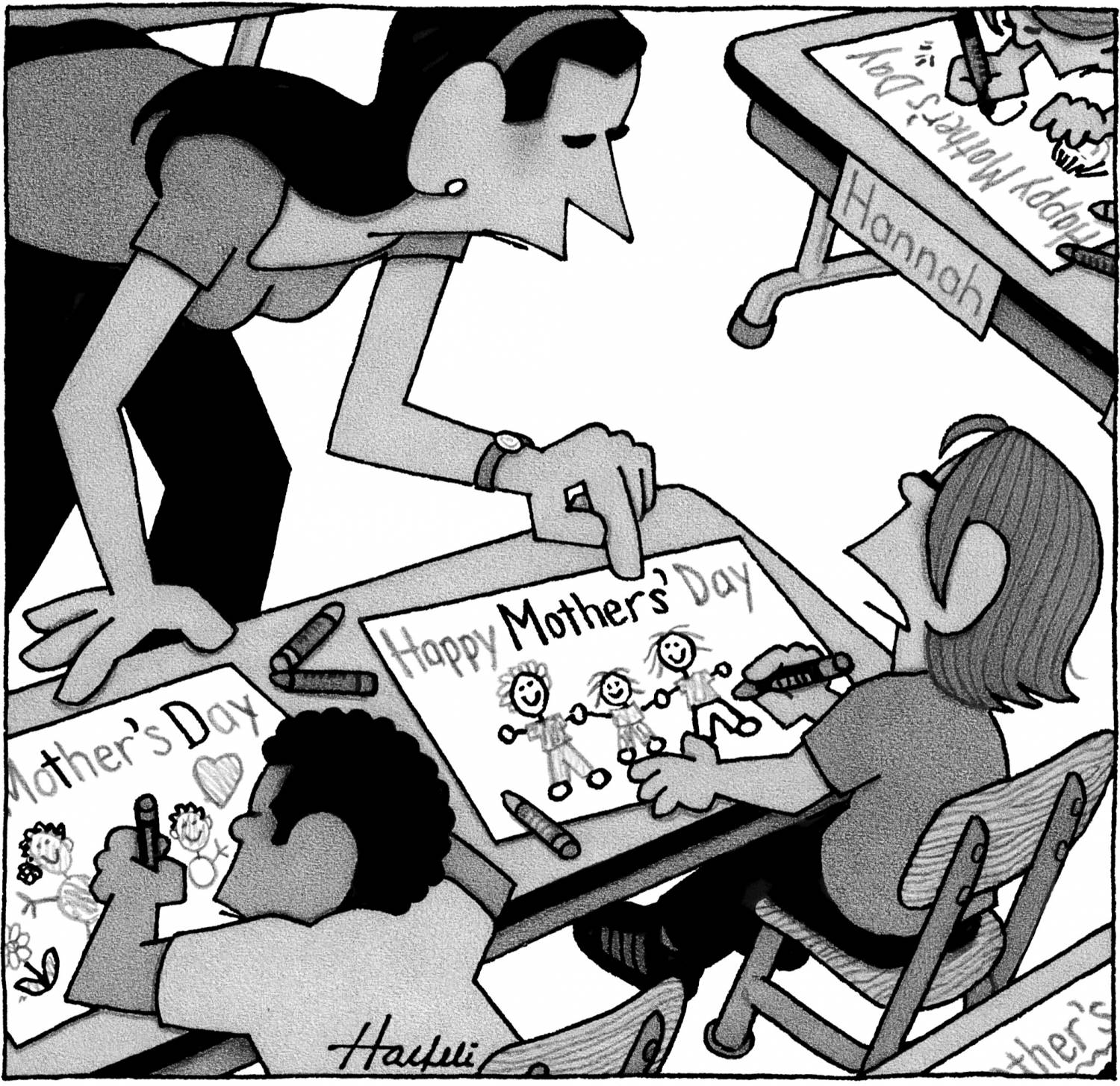

As our daughters get older, we know they’ll be like the kid in that New Yorker cartoon, explaining to a teacher where the apostrophe goes on a Mothers’ Day card. And with each passing May, the response from the center has been more positive and proactive, even though we also know that this is a conversation that we will likely need to have for many years to come.

But as annoying as these conversations may be, I realize how lucky my wife and I are to have this problem.

As we think about our predecessors in the LGBTQ rights movement, it’s important to note that while many were childless by choice, many others felt as though parenthood was simply out of their reach, either because the world was too hostile to LGBTQ people, because the technology was too expensive or because adoption agencies blatantly refused to think that LGBTQ people could be good parents (and a sad truth is that many still do today).

As a result, older LGBTQ adults experience higher rates of social isolation and have more precarious support networks than their non-LGBTQ contemporaries.

In addition to being less likely to have children, they are more likely to live alone and to be alienated from their families of origin – the predominant source of informal caregiving in this country. Moreover, the systemic discrimination that many LGBTQ older adults experience during their lifetime translates into fewer financial resources available to support themselves and worse health outcomes.